Around this time last year illustrator Rebecca Harry and I published a set of print-on-demand editions of our Ruby the Duckling books after the original editions went out of print. I'm pleased to announce that Pigs Might Fly!, one of my picture books with illustrator Steve Cox which recently went out of print, has just been re-published in the same format.

|

| The new square-format, print-on-demand edition. |

I was particularly keen to get Pigs Might Fly! in print again as it's one of my most popular books to read on school visits and its production is the focus of the How a Picture Book is Made presentation I do with Year 5 and 6 classes.

|

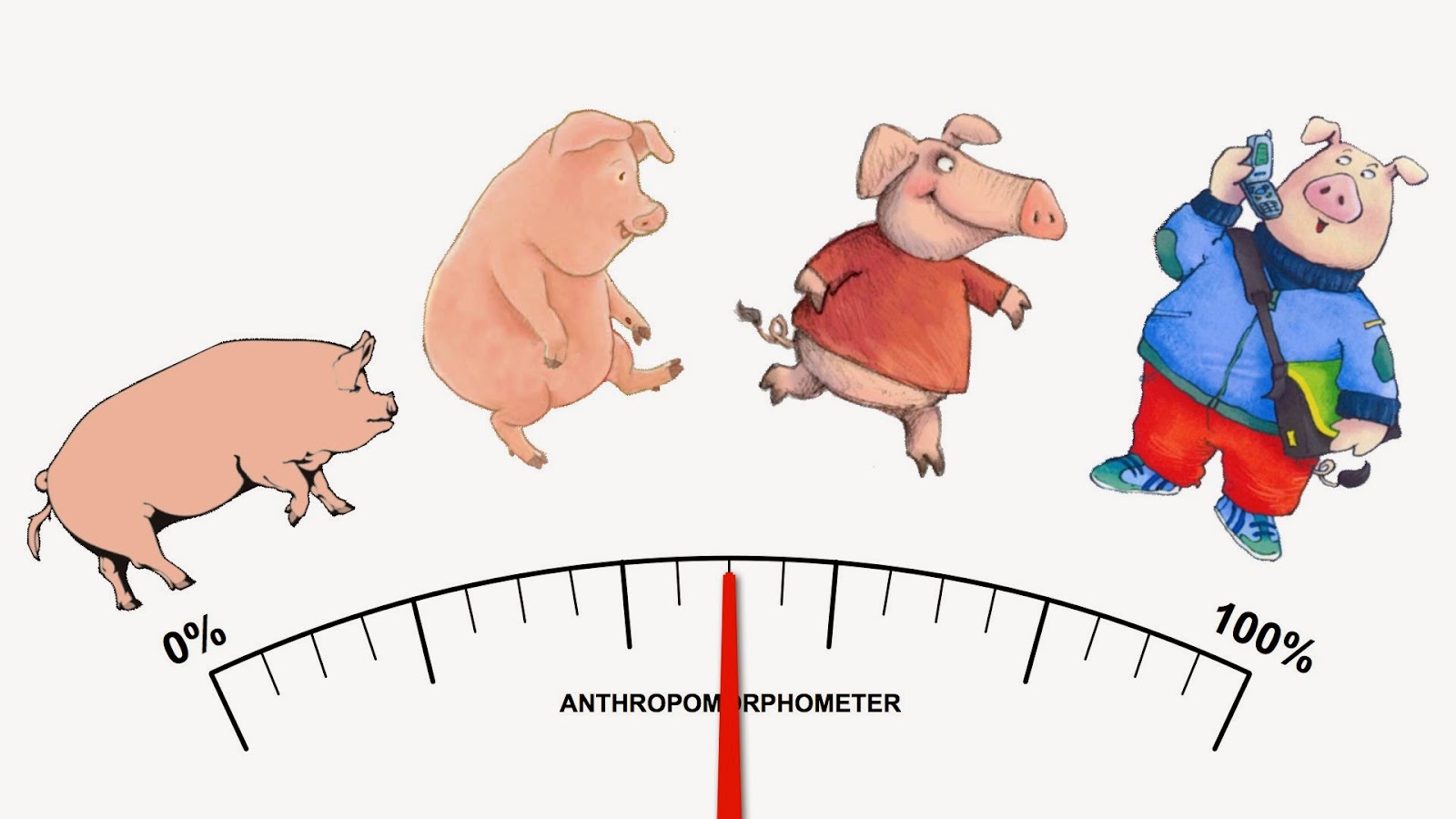

| This slide from my How a Picture Book is Made schools presentation shows some of the character designs Steve came up with before arriving at the final characters of Waldo, Woody and Wilbur. |

The book's popularity with young readers was also demonstrated when it won the “Books for Younger Children” category at the 2006 Red House Children’s Book Awards, a national children's vote awards organised by the Federation of Children’s Book Groups.

|

| Steve and I with my son and daughter and a very shiny trophy at the 2006 Red House Children’s Book Awards. |

The new edition has different page proportions to the original and has been re-typset using open source fonts. One of the advantages of having to re-work the layouts was that it gave us the opportunity to produce a 'directors cut' version of the book which incorporates a few improvements. For example: the original version had no imprints page, so the imprints details were printed on the opening spread. This gave the story a rather awkward start, so we created a new imprints/title spread for the new edition and reworked the opening text to cover both sides of the opening spread.

|

| While the original edition (top) had the imprint details printed on the opening spread, the new edition (bottom) has the imprints details on a new imprints/title spread. |

Most of the other changes were done in response to my experience of reading the book aloud in schools and are less easy to spot. So fans of the book can rest assured that the Big Bad Wolf is just as conniving as he was in the original edition …

… and Wilbur just as indomitable!

Here's what reviewers said about the book when it was originally published.

"A super book with a good storyline, amusingly told and wonderfully illustrated … a book children will want to look at again and again."

BOOKS FOR KEEPS

"Bright, breezy and fun with action on every page."

CAROUSEL

You can find out more about the book on this page of my website and download and print the new Spot the Difference activity sheet by clicking on the image below.